Artiklar från 2008 – till idag

John Neumeier with Helene Bouchet in the making of »Tatjana«. Photo Holger Badekow

John Neumeier: Ballet’s Guardian Angel

HAMBURG, TYSKLAND: There are few in the dance world as dedicated to the artform as John Neumeier. He has raised the Hamburg Ballet to international status and given them a vast repertoire of major ballets.

He has established a school, a youth company and is also one of the great conservers of our dance heritage through the Neumeier Foundation, founded in 2006.

I spoke to John Neumeier at the Foundation: part home part museum. When did your passion for collecting begin?

“I started collecting very young. In Milwaukee, where I was born, there were only visiting dance companies. I had this instinctive feeling that dance was very important for me but I couldn’t define what it was. I was 11 when I used my pocket money to buy my first book, The Tragedy of Nijinsky. Reading the story about Nijinsky’s life, a dancer became a real person with a destiny and with all of the attributes of a human being.”

“Ballet was something very magical but very distant because, of course, I was sitting upstairs in the cheapest seats. I tried to define dance but I needed some sort of evidence and collected what books I could find. As a dancer in Stuttgart in the mid-60s I started to buy prints and romantic lithographs because you could find them quite reasonably at that time and the collection began to grow. By the time I came to Hamburg in 1973 I started to be interested in auctions.”

Your collection must be very valuable?

“For me, the point of the collection is information: what did the people of the time see when they saw dance? I don’t think of the collection as something which has a monetary value but rather for its value in continuing the tradition. Saving these works and piecing them together like a puzzle means that not only myself, but generations after me, will be able to look at them and study them.”

Förstora bilden

Förstora bildenNijinsky’s series in black and red, sometimes called The Masks of War. Photo Holger Badekow (photo can be enlarged)

And the Nijinsky drawings?

“They suddenly became very important for me for this discrepancy between how Nijinsky was seen through the eyes of his contemporaries and how he, at the same moment, saw the world. The abstract drawings were made between 1917 and 1919. He had stopped dancing and was working in St Moritz by himself, quite desperate I think, because he couldn’t express himself as he used to. I think it was his absolute horror at the First World War that we see in the drawings.”

How does the artist link with the dancer?

“I went through various phases with Nijinsky. I was fascinated by the exotic, magnetic dancer with a great charisma: not only his technique but his presence must have been extraordinary. Then I reached a point where I appreciated what he was trying to do in choreography. He opened a new door to contemporary ballet and he was there before Martha Graham or Mary Wigman. With the publication of his diary we realised that here was an incredibly sensitive philosopher and then discovering the drawings, there was a fourth layer of information about this man."

"This is why I am so interested to have as many as possible – we now have, I think, 98 artworks. And they are not just scribblings of someone who is losing his mind: there is intention in them.”

While Nijinsky was a central part in the unique artistic synthesis of Diaghilev’s ballet productions he was a self-taught artist. Recently his art has begun to attract attention in its own right. Several of his paintings were included in the Inventing Abstraction exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2012. I asked if this was this the first time they were displayed in an art-historical context.

“No, in Hamburg in 2009 Nijinsky’s work was displayed with four other artists who were active in the same period. If the title had been in English it would have been Eye on Nijinsky – Nijinsky’s eye. He was an incredible draughtsman. Seeing the concrete drawings shows what a remarkable hand he had.”

Nijinsky's drawings often emanates from a circular movement, then taking the shape of a watchful eye.

In the catalogue to this exhibition Neumeier notes the relationship between avant-garde in choreography and in art. Michail Fokine’s Les Sylphides, a choreographed expression of the music that rejects narrative, finds its partner in abstract expressionism where pictorial forms find expression through the values of colour and form.

The Foundation also holds many images of Nijinsky from other artists including a drawing by Modigliani, a painting by Klimt and many sketches by Jean Cocteau. In a glass case there is a single petal from Nijinsky’s Spectre de la Rose costume and prominently placed is the famous bronze head of Nijinsky as Faun by Una Troubridge. A visit to the Neumeier Foundation is like visiting a past era where each remembrance is loved and cherished.

Maggie Foyer

8 September 2014

-

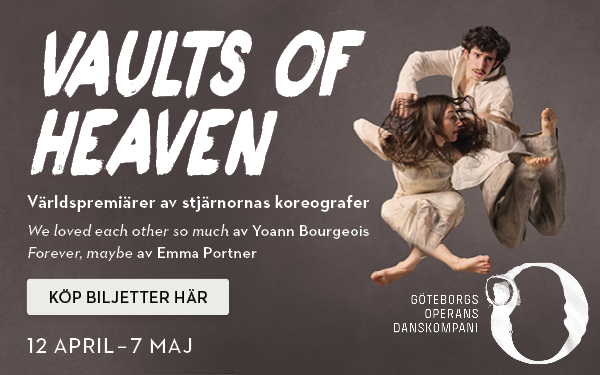

Yoann Bourgeois tillbaka till Göteborgsoperans Danskompani med ett sant styrkeprov

Efter fyra år är det dags igen för den franske koreografen Yoann Bourgeois att återvända till Göteborgsoperans danskompani. Denna gång för verket We loved each other so m...

-

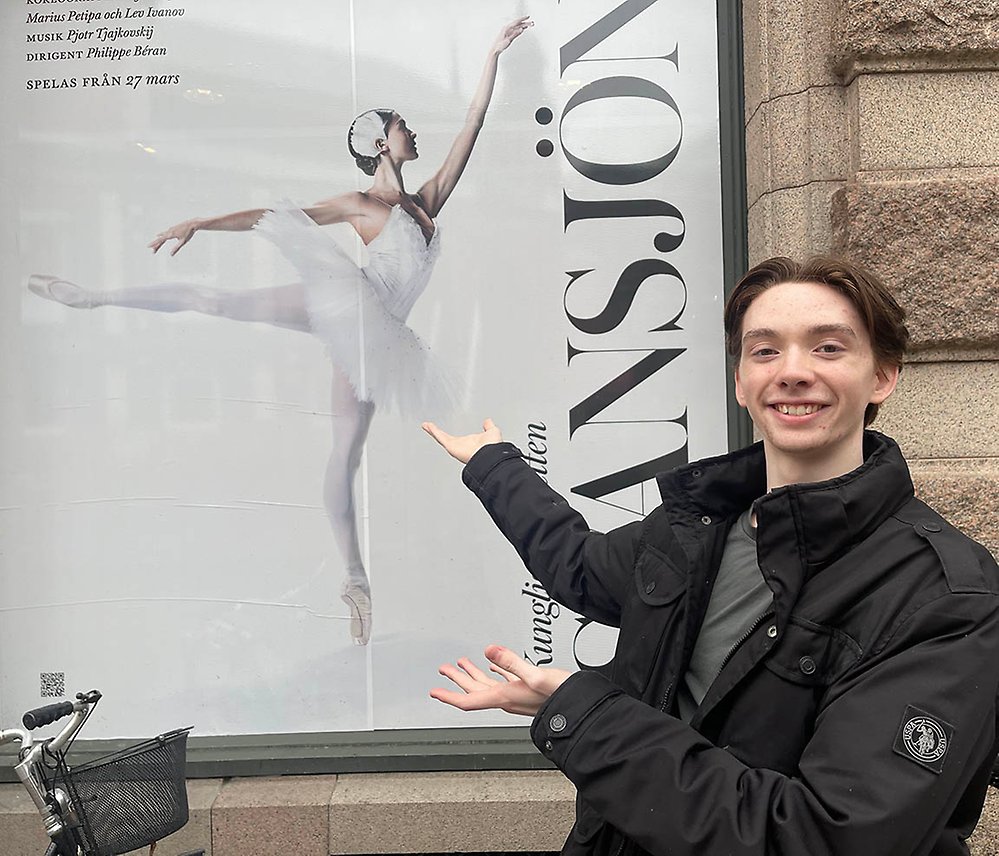

Spot on Darrion Sellman – dancing the leading role Siegfried in Swan Lake

In August last year Darrion Sellman arrived to Stockholm and joined the company. Darrion says: “It has been a change to come to Stockholm. A vibrant city, small but calme...

-

Kalle Wigle nyutnämnd solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin

Dansportalen gratulerar svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle som nyligen utnämnts till solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin.

-

Succéduo skapar nytt efter segertåg i Sverige och Europa

Intervju Hugo Therkelson och Tobias Ulfvebrand

-

40 år senare: En dansares triumf över tidens utmaningar

Förra sommaren ringde telefonen hemma hos Heléne i Kungsbacka. I lördags den 16 mars gjorde hon comeback på scenen efter nära fyra decenniers frånvaro och dessutom debut ...

-

Fart och kunnande på Pro Dance Galan 2024

Gamla operabyggnaden vid Bulevarden är ett Dansens Hus även om ett nyare Dansens Hus numera finns i Helsingfors, det också i centrum. Båda har sin publik, och båda behövs...

-

Svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle har stora framgångar i Berlin

Kalle Wigle är utbildad vid Kungliga Svenska Balettskolan och vid Royal Ballet School i London. Han fick anställning vid Operan i Stockholm 2016. Från hösten 2023 är han ...

-

Timulak/Portner två olika verk men med flera beröringspunkter

Från och med 9 februari och nästan en månad framåt dansar Kungliga Operan i Stockholm Totality in parts av Lukás Timulak och Bathtub Ballet av Emma Portner . De båda koreo...

-

På jakt efter det fullkomliga: nationens skickligaste dansare och – smultron!

Balettpedagogernas förbund ordnar vartannat år i Finland en nationell balettävling, i år 20-21 januari. Ett råd av balettkonstnärer med bakgrund som meriterade dansare ha...

-

Young Choreographers en föreställning där dansare från Kungliga Operan koreograferar

Tisdagskväll på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm och det är premiär för Young Choreographers. Dansare från ensemblen får chansen att pröva egna idéer och koreografera sina kol...

-

Operans VD Fredrik Lindgren: På sikt vore det fantastiskt att få ett nytt Operahus i Stockholm

Kungliga Operan är en 250-årig kulturinstitution i hjärtat av Stockholm. Över 500 anställda levererar hyllade föreställningar med utsålda hus. Dansportalen har samtalat m...

-

Från Svenska balettskolan i Göteborg till ungerska Statsoperan i Budapest

Det började med 6 år på Svenska balettskolan i Göteborg med start i årskurs fyra för Mattheus Bäckström och Auguste Marmus . Mattheus gick ut 2017 och hade då blivit antag...

-

Joseph Sturdys verk Lucid Episode inleder nyårsgalan på Kungliga Operan

Vi befinner oss på Kungliga Operan. Det pågår repetition med två dansare som är med i Joseph Sturdy s verk Lucid Episode som inleder själva nyårsgalan den 31 december.

-

Göteborgsoperan sjunger in julen med En Julsaga

Göteborgsoperan avslutar december månad med nypremiär på musikalversionen av Dickens En julsaga . Föreställningen är breddad med humor och medmänsklighet. Adams julsång bl...

-

Nötknäpparen, nypremiär på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm efter fyra års uppehåll

Det är nypremiär av Pär Isbergs Nötknäpparen på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm. I salongen sprids julstämningen och publiken får vara med om en dansant och virvlande berätte...

-

Giovanni Bucchieri – en konstnärlig kameleont

Det är premiär för filmen 100 ÅRSTIDER . Upphovsmannen har gått från dansare till multikonstnär. Möt regissören Giovanni Bucchieri i en personlig intervju med Dansportalen...

-

”Mycket talar för att vi inte kommer att kunna vara kvar där vi är nu,” säger Hans Lindholm Öjmyr, ny chef för Dansmuseet

Hans Lindholm Öjmyr är filosofie doktor i konstvetenskap och har skrivit en avhandling om scenografi på 1800-talet vid Kungliga Teatern/Operan. Hans har tidigare varit av...

-

In a heartbeat, ny världspremiär på Göteborgsoperan

In a heartbeat bekrivs som ett pulserande dansbubbel och på Göteborgsoperan är det nu världspremiär allhelgonaafton på stora scenen för Hofesh Shechter s verk Wild poetry ...

-

Le Corsaire, svensk premiär på Kungliga Operan med virtuos dans och teknisk skicklighet

När Kungliga Operan för första gången ger Le Corsaire bjuds det på en dansfest. Verket som hade sin urpremiär på Parisoperan 1856 kommer till liv och publiken får möjligh...

-

New talents join the Royal Swedish Ballet

Eleven young dancers join the Royal Swedish Ballet company this season. We are thrilled to see them on stage! On October 27, this season's grand premiere of Le Corsaire w...

-

Där låg onekligen ett skimmer över Gustavs dagar

I Livrustkammarens visas den största satsningen på flera år på en tillfällig utställning i samarbete med Kungliga Operan – öppnas 20 oktober, Teaterkungen: Prakten, makte...

-

Attityder som uppskattades

I Drottningholmsteaterns déjeunersalong gavs i september in innehållsrik, högklassig presentation av ett forskningsprojekt som genomförs på Kungliga Musikhögskolan och fi...

-

Spot-on Kentaro Mitsumori, dancer with the Royal Swedish Ballet

Kentaro Mitsumori has been a member of the Royal Swedish Ballet since 2017. We have seen him in many roles, in Swan Lake, Cinderella, Don Quijote, The theme and variation...

-

Kalle Wigle-Andersson får stipendium från Jubelfonden

Kalle Wigle-Andersson: Jag är utbildad och diplomerad vid Royal Ballet Upper School, London 2016. Innan dess gick jag på Kungliga Svenska Balettskolan 2006-2014. Sedan mi...

-

Wicked, musikalen om häxorna i Oz

Göteborgsoperan inleder sin höstsäsong med den mytomspunna succémusikalen Wicked. Exakt tjugo år efter Broadwaypremiären 2003, sätts den nu upp för första gången i Sverig...

-

Balettgalan i Villmanstrand är sensommarens succéevenemang

Balettgalan i Villmanstrand vid Finlands östra gräns gavs i år för 12:e gången och var igen en succé med både nationella och internationella dansare. Galans grundare och eldsjäl Juhani Teräsvuori hade...

-

Möte med Fredrik Benke Rydman om ”The One”

Det är mannen från dansgruppen Bounce, koreograf till egna versioner av Svansjön och Snövit bland mycket annat. Jag träffar Fredrik Benke Rydman på en liten thaikrog mellan repetitionspassen.

-

“A new look at it” – Lady MacMillan about Manon with the Royal Swedish Ballet

As part of the 250-year jubilee program of the Royal Swedish Opera and as a tribute to the long-lasting cooperation between the Royal Swedish Ballet and world-renowned English choreographer Sir Kennet...

-

Urpremiär av episkt dansverk på Norrlandsoperan

Den 1 september bjuder Norrlandsoperan på säsongsuppstart för dans med urpremiär av den episka föreställningen Remachine signerad koreografen Jefta van Dinther . Ljus, ljud, röst, koreografi och scenog...

-

Contemporary dance av Hofesh Shechter på GöteborgsOperan

Danskväll med intensiv klubbfeeling, smittande glädje och en upplevelse som börjar redan utanför operahuset.

-

Julia Bengtsson – internationell barockdansös från Sverige

Höjdpunkten under årets förnämliga Opera- och musikfestival på Confidencen var iscensättningen av Jean-Philippe Rameaus opera Dardanus . I en annan föreställning, A Baroque Catwalk , gjorde Julia Bengts...

-

The Royal Ballet School Delights

Written on the faces of the dancers as they spin and leap in the ecstatic final moments of the Grand Défilé , is the smile that says, ‘I did it’. It’s what I look forward to year after year and it neve...

-

Ett barockt spectacle på Confidencen

Confidencen Opera & Music Festival inleds den 27 juli med Jean-Philippe Rameaus mästerverk Dardanus, som genom ett gediget arbete får sin nordiska premiär på Sveriges äldsta rokokoteater – 284 år efte...

-

Möt Vivian Assal Koohnavard dansare vid Staatsballett Berlin och aktivist

I Berlin träffade jag och arbetade med Vivian Assal Koohnavard. Vivian fick sin dansarutbildning i Sverige och Tyskland. Hon har varit anställd vid Berlin Staatsballett sedan 2018. Där deltar hon i de...

-

Peter Bohlin om Kungliga Svenska Balettskolans uppvisningsföreställningar

Skolårets sista föreställningar på KSB var uppdelade i fyra program. Några koreografier var storartade, andra inte. Här, mot slutet, ett försök att resonera om anledningar till detta.

-

Dans i Stockholm Early Music Festival

I 2023 års version av Stockholm Early Music Festival , den tjugoandra i ordningen, ingick två dansföreställningar. I fablernas värld , en kort musikalisk och dansant barockföreställning med Folke Danste...

-

.jpg)

Suite en Blanc av Estoniabaletten med fina danssolister

Jag hade möjligheten att två gånger se en ny balettafton med två verk. Black/White innehöll “Open Door ” av polskan Katarzyna Kozielska och Serge Lifars kända och genuina Suite en Blanc . Den sistnämnda...

-

Marie Larsson Sturdy Carina Ari Medaljör 2023

På Carina Ari-dagen 30 maj tilldelades Marie Larsson Sturdy Carina Ari-medaljen för hennes mångåriga och engagerade insatser inom Dans i Nord – en vital verksamhet som under mer än 20 år har främjat m...

-

Manon: An evening to treasure

Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon created in 1974, continues to weave its magic providing a slew of dramatic roles against a volatile and violent backdrop. The Royal Swedish Ballet first presented the ballet ...

-

Instudering av Mats Eks ”En slags” med Staatsballett Berlin

I april 2022 reser Koreografen Mats Ek och jag till Berlin för att hålla audition med dansarna vid Staatsballett Berlin på Deutsche Oper. Vi ska välja dansare till verket ”En slags” av Mats Ek. Premiä...

-

Marianne Mörck berättar sagan om Peter Pan med Svenska Balettskolan

Till vårens uppsättning av Peter Pan och Wendy på Lorensbergsteatern är en av gästartisterna ingen mindre än Marianne Mörck . Efter första repetitionen tillsammans med baletteleverna på svenska baletts...

-

Det var en gång på Grand Hôtel, musikalen som återupptäckts

Göteborgsoperan avslutar sin vårsäsong med premiär den 22 april på Paul Abrahams musikal Det var en gång på Grand Hôtel. Musikalen som legat gömd fram till 2017. En föreställning fylld av dans och mus...

-

Virpi Pahkinen: "Precision möter osäkerhet, matematik möter mystik"

Change – den nya dansföreställningen av och med Virpi Pahkinen – är uppbyggd enligt principen 5 + 5 + 5, dvs koreografi/ljus/musik. Strax före fredagskvällens premiär på Kulturhuset Stadsteatern fick ...

-

För dansens skull dansas Pro Dance galan

Den anrika Aleksandersteatern fylldes åter av dansfolket som ville stödja dansen och dess utövare via föreningen Pro Dance med att köpa biljetter till den årliga galaföreställningen. Artisterna uppträ...

-

Anthony Lomuljo – om hur det är att igen dansa Romeo – 10 år senare

10 år har gått sedan urpremiären av Mats Eks Julia & Romeo på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm. Då liksom nu dansar Anthony Lomuljo rollen som Romeo. När Dansportalen några dagar innan premiären träffar An...

-

Hur bygger vi upp oss själva igen när allt är förstört–Johan Inger om Dust and Disquiet på Göteborgsoperan

Danskvällen Touched visar två världspremiärer på Göteborgsoperan, Dust and Disquiet av Johan Inger och To Kingdom Come av det nederländska syskonparet Imre och Marne Van Opstal . Naturkatastrofer runt ...

-

Mats Ek om Mats Eks Julia & Romeo

Operans Balettklubb gästades lördag 25 mars av koreografen Mats Ek och dansare inför nypremiären av ”Julia & Romeo” på Kungliga Operan. Verket uppfördes på teatern för första gången 2013. Det har ocks...

-

Nordens största danstävling lockade 44 dansare

Äntligen! Det är vad de flesta kände när tävlingen Prix du Nord genomfördes på Kronhuset i Göteborg.

-

Young choreographers en bra plattform för nya idéer

En alldeles särskild glädje med workshopartade föreställningar är att man får se dansarna på riktigt nära håll. Så var fallet på Operans Rotunda 16 och 18 mars, i ett program med sju koreografer och 3...

-

%20Agathe%20Poupeney%20OnP%20-BONP-D%C3%A9fil%C3%A9.jpg)

Gala till minne av den lysande dansaren Patrick Dupond

Under februari var det tre utsålda galor på Palais Garnier i Paris, till minne av dansaren och balettchefen Patrick Dupond . För programmet på galan, se nedan!

-

Madeleine Onne: Man får slåss för sin konstart

Madeleine Onne har varit balettchef i Stockholm, Hongkong och Helsingfors. Dansportalen har pratat med Madeleine om bland annat tiden i Hongkong, Helsingfors och om Stockholm 59°North. Men på vår förs...

-

Triple Bill at the Ballet. What's not to Like?

The feel-good factor was in abundance at the Royal Opera House in Stockholm with a triple bill to send the audience home with a smile.

-

Elever från Kungliga Svenska balettskolan tävlade i årets Prix de Lausanne

Sveriges kandidater i Prix de Lausanne kommer båda två ifrån Kungliga Svenska balettskolan. Theodor Bimer och Alexander Mockrish. Tävlingen firar 50 årsjubileum lite sent då pandemin stoppat ett flert...

-

.jpg)

12 songs + Ane Brun och Kenneth Kvarnström på Göteborgsoperan

Första helgen i februari är det premiär för 12 songs + på Göteborgsoperan. Ett scenkonstverk skapat genom samarbete mellan 18 dansare och en av Nordens främsta koreografer, Kenneth Kvarnström, i något...

-

Jubileumsgala med Operan och Kungliga Baletten 250 år

Kungliga Operan öppnade med en fantastisk gala 18 januari med 23 olika programpunkter som innehöll opera, balett och teater. Under 250 år har framförts 54 900 föreställningar och vad var mer naturligt...

Notiser

- Kulturnatt Stockholm

- Kulturnatten på Kungliga Operan – en upplevelse för alla sinnen

- Hösten på Kungliga Operan – en helande kraft i en orolig tid

- Bröder och systrar förenas på dansgolvet under årets Up North-helg, 4-5 maj på NorrlandsOperan

- Det här ger GöteborgsOperans danskompani säsongen 2024/2025!

- La saison 24/25 de l'Opéra national de Paris est en ligne !

FÖLJ OSS PÅ

-

Kreativ lyskraft hos GöteborgsOperans Danskompani

GöteborgsOperans danssäsong 2024/2025 blir en virtuos upplevelse med kreativ briljans. Strålkastarljuset riktas mot starka kvinnliga röster och det blir både raffinerade ...

-

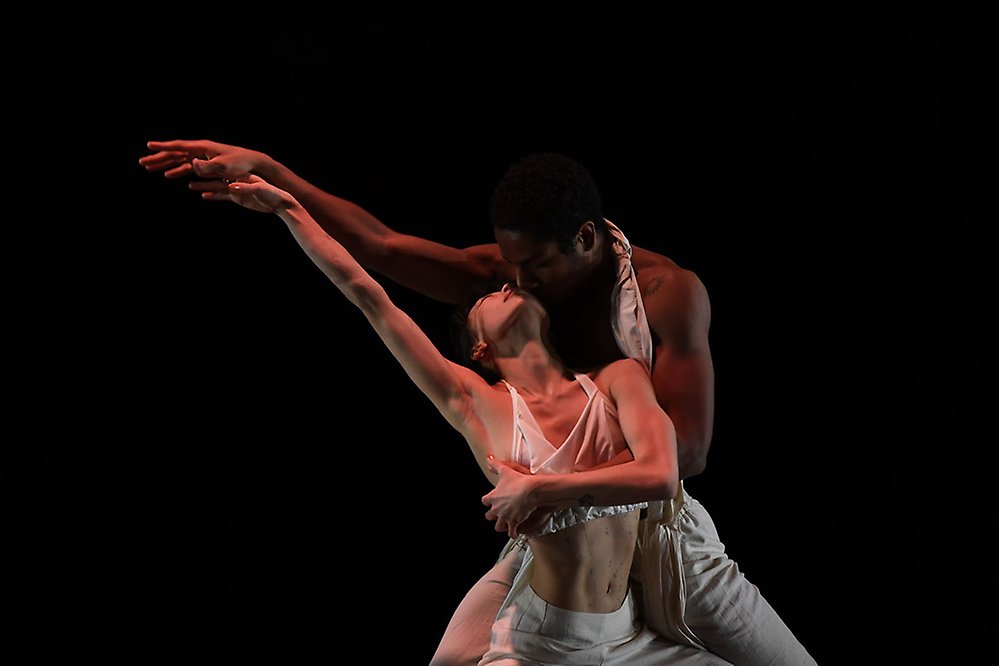

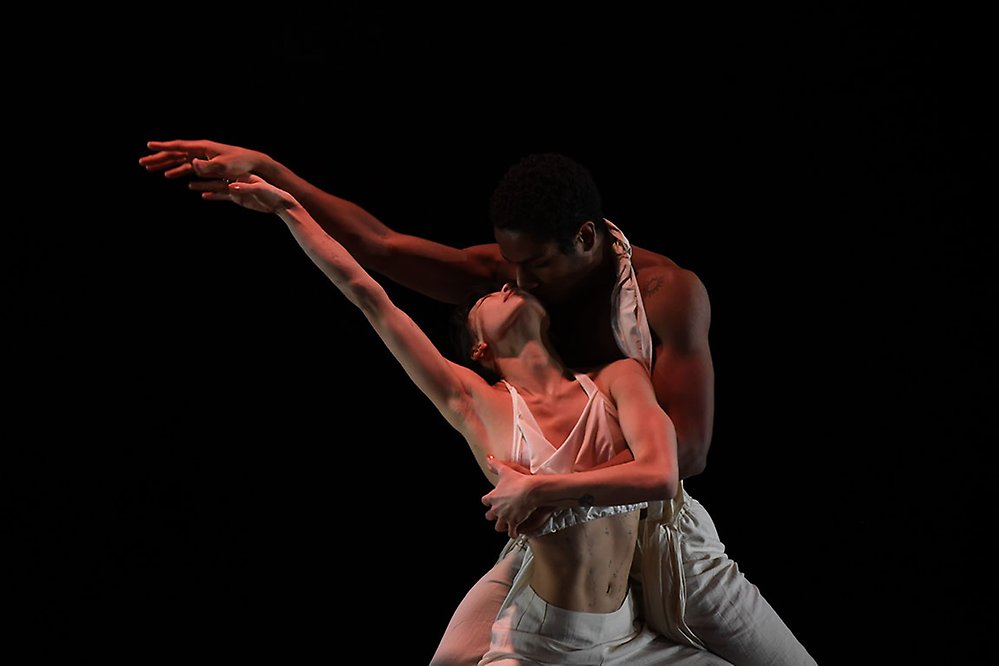

Dansarna berör på djupet med sin dansade kyss

Sommaren 2022 turnerade Don't, Kiss .Skånes utomhus i Skåne och Köpenhamn. 23 mars 2024 får föreställningen nypremiär på Skånes Dansteater, denna gång som inomhusverk med...

-

Spot on Darrion Sellman – dancing the leading role Siegfried in Swan Lake

In August last year Darrion Sellman arrived to Stockholm and joined the company. Darrion says: “It has been a change to come to Stockholm. A vibrant city, small but calme...

-

Kalle Wigle nyutnämnd solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin

Dansportalen gratulerar svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle som nyligen utnämnts till solist vid Staatsballett i Berlin.

-

Succéduo skapar nytt efter segertåg i Sverige och Europa

Intervju Hugo Therkelson och Tobias Ulfvebrand

-

40 år senare: En dansares triumf över tidens utmaningar

Förra sommaren ringde telefonen hemma hos Heléne i Kungsbacka. I lördags den 16 mars gjorde hon comeback på scenen efter nära fyra decenniers frånvaro och dessutom debut ...

ANNONS

Ur Dansportalens arkiv

-

Nurejevs Svansjön på Stockholmsoperan – en version aldrig tidigare spelad i Sverige

Inför Kungliga Balettens premiär på Svansjön i koreografi av Rudolf Nurejev gästades Operans Balettklubb av iscensättaren Charles Jude och dansaren Calum Lowden.Charles J...

ANNONS

-

Fart och kunnande på Pro Dance Galan 2024

-

Svenske dansaren Kalle Wigle har stora framgångar i Berlin

-

Timulak/Portner två olika verk men med flera beröringspunkter

-

På jakt efter det fullkomliga: nationens skickligaste dansare och – smultron!

-

Young Choreographers en föreställning där dansare från Kungliga Operan koreograferar

-

Operans VD Fredrik Lindgren: På sikt vore det fantastiskt att få ett nytt Operahus i Stockholm

-

Från Svenska balettskolan i Göteborg till ungerska Statsoperan i Budapest

-

Joseph Sturdys verk Lucid Episode inleder nyårsgalan på Kungliga Operan

-

Göteborgsoperan sjunger in julen med En Julsaga

-

Nötknäpparen, nypremiär på Kungliga Operan i Stockholm efter fyra års uppehåll

-

Giovanni Bucchieri – en konstnärlig kameleont

-

”Mycket talar för att vi inte kommer att kunna vara kvar där vi är nu,” säger Hans Lindholm Öjmyr, ny chef för Dansmuseet

-

In a heartbeat, ny världspremiär på Göteborgsoperan

-

Le Corsaire, svensk premiär på Kungliga Operan med virtuos dans och teknisk skicklighet

-

New talents join the Royal Swedish Ballet

-

Där låg onekligen ett skimmer över Gustavs dagar

-

Attityder som uppskattades

-

Spot-on Kentaro Mitsumori, dancer with the Royal Swedish Ballet

-

Kalle Wigle-Andersson får stipendium från Jubelfonden

-

Wicked, musikalen om häxorna i Oz

Redaktion

dansportalen@gmail.com

Annonsera

dansportalen@gmail.com

Grundad 1995. Est. 1995

Powered by

SiteVision